Fiona Banner, Barry Flanagan, Toby Tobias Kidd, John Latham, Cally Spooner, Anne Tallentire: EXTROSPECTION curated by David Thorp

Examination or observation of what is outside oneself.

In 1969 in an article ‘Situational Aesthetics’ published in the British magazine Studio International, artist Victor Burgin proposed that the concepts of artistic object and artistic form should be disassociated from fabricated things and redefined in terms of the ‘structures of psychological experience’[1] He argued that the ‘new’ art of the era was positioned within a linguistic structure and that its form ensued from its message rather than materials. This art results from systems that, when applied by the artist, have the capacity to generate objects in which particular concepts can be demonstrated rather than manifested expressively in material form and that by revising our attitude towards materials, aesthetic objects can be sited partly in real space and partly in psychological space.

In the same year the UK based collaborative practice Art and Language formed The Society for Theoretical Art and Analyses and went on to publish the magazine Art-Language - subtitled ‘the journal of conceptual art’.[2] Rejecting the production of art objects altogether, Art and Language instead concentrated on philosophical debate that involved a communal discourse among artists. They explored the idea of whether or not writings about the language of art could plausibly be considered as art. Arguing that Cubist collage and Duchamp’s ready-mades, for example, set precedents proving that what at first sight appears sacrilegious is the logical and inevitable development of inquiring into the nature and conventions of art which it is the job of the artists to do.

The discussion of such theories however never completely overcomes the sense that they are producing an ingrown dialogue only ever fully appreciated by other artists or that small group of art world specialists who influence the direction of art. For some this is of no matter but for others it provokes such arguments as the notion that the void between the artist and audience is only bridged successfully if the artist does not think but feels and has the craft skills to represent those feelings. This was superseded by the middle of the last century when Harold Rosenberg recognised that artworks no longer manifested such recognisable qualities and identified the anxiety of an audience confronted by an unfamiliar object bearing the label ‘art’. And with Marcel Duchamp’s assertion that a work of art is completed by its reading by an audience. ‘The artist Duchamp said, is a ‘mediumistic being’ who does not really know what he is

[1] Originally published in Studio International, vol.178 no. 915, October 1969, pp.118-21

[2] Jo Melvin, "The British Avant Garde: A Joint Venture Between the New York Cultural Center and Studio International Magazine", British Art Studies, Issue 3

The second issue of Art-Language dispensed with the subtitle “the journal of conceptual art” because it suggested inclusivity of the diverse practices loosely configured by the rubric of the term.

The Society for Theoretical Art and Analyses merged with Art & Language in 1970. Charles Harrison became editor of Art-Language in 1971. By the mid-1970s some twenty people were associated with the name, divided between England and New York. From 1976, however, the genealogical thread of Art & Language’s artistic work was taken solely into the hands of Baldwin and Ramsden, with the theoretical and critical collaboration of these two with Charles Harrison who died in 2009.

Conceptual art was never an autonomous movement, although it challenged the norms and authority of modernism and built on some of the precedents of Minimalism, it was at first too amorphous to be classified as Conceptualism. Nevertheless various attempts have been made to identify attitudes that are important (if not necessary and sufficient) conditions of conceptual art. Back in 1967 Sol LeWitt was asked by to write an essay on conceptual art for the magazine Art Forum. LeWitt’s ‘Paragraphs on Conceptual Art’[2] is as much a manifesto as an essay especially when considered alongside his ‘Sentences on Conceptual Art’ originally published in the first edition of Art-Language.[3] Both are often referred to, usually with reference to his assertion that ‘In conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work’.[4] He writes that these ideas need not be complex, indeed successful ideas are frequently simple and, while these ideas are discovered intuitively, their success is a result of their appearance of inevitability as if there could be no other outcome to the process of conception and realisation with which the artist is concerned. At the same time this process is contradictory and not necessarily logical. It can be paradoxical and humorous and challenge the high seriousness of the preceding more expressive and materially based art forms. It is not seeking profundity but rather enquiring into just what art might look like if the idea dominated all other elements in its realisation. Conceptual artists ‘Leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach’[5] he says and while ‘all ideas are art if they are concerned with art and fall within the conventions of art’[6] the artist changes these conventions by refashioning subjective perceptions of what it could be. If art is stripped of its deep conventional trappings how will it appear? According to LeWitt, this is something which the artist cannot perceive until the work is finished and even then the artist may not understand their own art, their perception is no better or worse than that of others. A somewhat anarchic, contradictory and playful process embraces irrational thought as it makes imaginative leaps structured within a system.

Conceptual art has long been associated with high seriousness in art. The early writing of Victor Burgin and Art and Language for example is highly theoretical, dense, full of philosophical and academic terminology that counters ‘the anti-intellectualism of English and American artists’[7], while the potential to play with

[1] Calvin Tomkins, Ahead of the Game, Marcel Duchamp, Penguin Books 1968 p 13

[2] Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art, Art Forum, vol 5 no 7, June 1967. pp. 79-83

[3] Sol LeWitt, Sentences on Conceptual Art, Art-Language, vol.1 no.1, May 1969, pp11 -13.

[4] Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art, ibid

[5] Sol LeWitt, Sentences on Conceptual Art, ibid

[6] Sol LeWitt, Sentences on Conceptual Art, op.cit

[7] See Robert Motherwell, The Modern Painters World, Dyn 1, no 6 (November 1944) pp9-14. The anti-intellectualism of English and American artists has led them to the error of not perceiving the connection between the feeling of modern forms and modern ideas.

ideas in a humorous or poetic way is a tendency that has to some extent been marginalised in the broad canon of conceptual art. As David Batchelor points out in an essay about Sol LeWitt ‘Clearly Conceptual Art meant many things to many people, but much of it is marked by a kind of critical self-consciousness concerning the relations between different modes of representation – visual and verbal in particular’.[1]

Referring to Sol LeWitt’s ‘Paragraphs on Conceptual Art’ in his book ’Conceptual Art’, Tony Godfrey[2] makes the point that LeWitt’s statement works best when applied to his own work and those following a very similar line. ‘Soon he was having to make a distinction between conceptual art, which was what he did, and Conceptual art (with a capital C) which was what others did.’[3] By the middle of the 1970s Conceptual art had become a movement, Conceptualism, after all. Its amorphous nature that had once stopped any group categorisation from being established had in the end become the motif of a movement. It embraced Land Art, Arte Povera, Anti-form and so on (Godfrey lists seven categories).[4] Its reach extended to every part of the world taking on a different complexion in different cultural contexts. The rigorous analysis of language paramount among artists in the US and UK gave way to more poetic resonances in continental Europe, the complete dematerialisation of the object was rebutted by monochrome painting.

Eventually Conceptual art became a lay term for contemporary art. In doing so the specificity embodied in Burgin’s situational aesthetics and the stance of Art and Language, for example, was sacrificed to an accessible idiom, an umbrella catchall that simplifies the fragmented and variegated status of fast moving developments in art practice. Given that Conceptual art had gradually gathered so many international aesthetic initiatives in its thrall it is of no surprise that this occurred. For those non-specialists who are ill disposed to study the minutiae of contemporary art these small distinctions mean nothing. However, the core principles that intrinsically underpinned Conceptual art, for argument’s sake: the dematerialisation of the object; an analysis of language; the poetic potential inherent in everyday objects; an emphasis on process; an anti-authoritarian attitude; a questioning of the nature of art; are conditions that have endured and inform those artists who are the successors to LeWitt and his contemporaries.

John Lennon and Charlie Chaplin get a mention in Tony Godfrey’s book but John Latham and Barry Flanagan do not. Admittedly, Chaplin is only mentioned as the object of an attack by Guy Debord and his Lettristes friends,[5] while Lennon plays a more prominent role, appearing five times in the book and at one point sharing a page with Victor Burgin. By contrast, in the catalogue for Tate’s 2016 exhibition ‘Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1979’,[6] John Latham and Barry

[1] David Batchelor, Within and Between, Sol LeWitt Structures 1962-1963, Museum of Modern Art Oxford, 1993. p.20.

[2] Tony Godfrey, Conceptual Art, Art and Ideas, Phaidon Press Ltd. 1998.

[3] ibid. p.13

[4] op.cit. p. 150.

[5] op.cit. p.59

[6] Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1979, Tate Publishing, London, 2016

Flanagan make early appearances in the first essay ‘New Frameworks’[1] and on many other occasions throughout the publication. This discrepancy that demonstrates that the nebulous nature of Conceptual art, and which artists fit the bill, means that it is hard to categorise and thus readily lends itself to the shorthand of the popular art press.

One of the most well documented acts of anti-authoritarian Conceptual art is that of Latham’s encounter with Clement Greenberg’s collected essays Art and Culture and St Martins School of Art library in London. It has been recounted many times but for the sake of this essay I shall briefly relate it once more. As a tutor at St Martins, Latham withdrew Art and Culture from the school library and used it as the basis of an event in which he and some others chewed up pages of the book. The remains were returned to the college library in a test tube. The party/event was called Still and Chew because the transformation of the chewed up pages was through distillation involving the introduction of yeast, to model the process of producing alcoholic spirits. As a result of this Latham was dismissed as a tutor from the college. His aide in this act was the young Barry Flanagan who designed the invitation and took part in the event.[2] Latham was a tutor of drawing in the painting department at St Martins and Flanagan encountered him there as a student. Despite the fact that, surprisingly, sculptors did not have access to a drawing lecturer, Flanagan joined Latham’s drawing classes unofficially and they became friendly. Latham was deeply engaged in theories about time and space and notions about the fundamental essence of creation from which he developed the concept of the ‘Least Event’. Latham considered Least Events to be the fundamental building blocks of the world, the most minimal departure from a state of nothing from which all things flowed forward in time. His discovery of the spray can as a painting tool provided him with the means to illustrate this condition in one-second drawings that captured the instant when a cloud of minute drops of paint hit a white board.

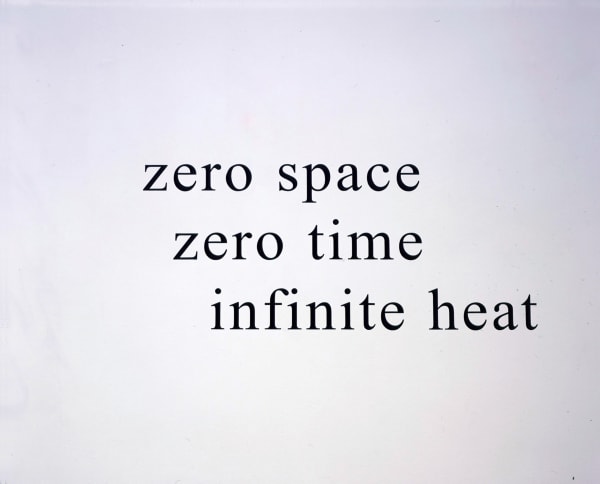

Two of Latham’s works ‘Rephrase: zero space zero time, infinite heat’ and ‘THE MYSTERIOUS BEING KNOWN AS GOD is an atemporal score, with a probable time-base in the region of 1019 seconds.’ are part of a larger body of work collectively entitled ‘God is Great’. They concern themselves with the cosmopoetics of the baffling and essential subject; the origin of creation and the universe. Latham devoted a life’s work to the creation of a cosmology that aimed to unite art and science through his theory of origins reflected in Einstein’s description of the coming into being of the universe from a state of ‘zero space, zero time, infinite heat’.[3] In ‘God is Great’ he attempted to found a compatible relationship between the ethical goals of humanity and the dominant scientific theories of the universe. These text works are remade each time they are shown. Stuck to the wall with adhesive lettering they

[1] Andrew Wilson, New Frameworks, Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1979, Tate Publishing, London, 2016 p.15

[2] The remaining detritus complete with bottles, book and all the correspondence related to the event along with a case, was made into a work by Latham, Still and Chew/ Art and Culture, now part of MoMA’s collection in New York.

[3] The phrase “zero space, zero time, infinite heat” was taken to epitomise the postulate of a singularity at the beginning and possibly the end of the universe taken from an extrapolation of Einstein’s field equations. John saw this as expressing features of his own view though obscured by its linguistic formulation. John’s rephrasing took zero space zero time to be nonextendedness, and infinite heat to be a least impulse to extend. Noa Latham in correspondence with the author. August 2020

present the minimum object nature that an artwork can have and still exist in the material world.

Flanagan was influenced by Latham’s experimental and anti-authoritarian approach but, ever the bricoleur, he drew upon a broader range of sources and ideas.

Both artists inclined, however, towards an open ended process when making art that, although it could result in objects, was not necessarily contingent upon producing a discrete concrete artwork as an end. They were self-contained within hermetic systems; Latham’s the more arcane; Flanagan’s more determined by his alignment with Alfred Jarry’s philosophy ‘pataphysics. This ‘science of imaginary solutions’ fitted Flanagan’s iconoclastic bent and his sense of the absurd, whereas Latham, although his work is shot through with an anarchic humour, which both shared, would never be deflected from the high seriousness of his endeavour.

Of course Flanangan was intensely serious about his work but he brought a lightness of touch to the realisation of his ideas. Running through all of Flanagan’s work is a poetic sensibility that filters Arte Povera attitudes into an approach that ensues from a quite specific reaction to formalism; Greenberg, and indeed Anthony Caro (the éminence gris of the Advance Sculpture Course); which has a lot to do with being in London at a particular time and in a particular place (1964-66 in St Martins on the Charing Cross Road). This London orientated development of Conceptual art brought within its purview other young artists who could loosely be grouped together under a banner of Conceptualism. Humour; irony; a rejection of the object; were all characteristics of these artists. Flanagan, singularly, imbued such qualities into materials. Managing to make objects that, while concrete, abjured the object nature of sculpture. While this may sound like an impossible task, its encapsulation of the contradictions implicit in any absurd activity provided it with the plausibility needed to be convincing.

Each of Flanagan’s pieces in ‘Extrospection’ demonstrates an aspect of his work that emphasizes various perspectives on essentially the same issue: to mount a critique of the object by producing a successive assortment of formless objects. Even Flanagan’s work ‘a hole in the sea’ 1969 is suggestive of the object because in order to make the negative space Flanagan embedded a Plexiglass cylinder in the sand and filmed it as the tide rolled in. His critique of the object employs the stuff of sculpture but in these early works he relinquished control of the outcome. Flanagan made several sculptures using sand, allowing the humble material from the building site to make its own form when poured or piled up. The immediacy of its advent as a presence in the gallery; its essential malleability, as in ‘sand pour’ 1968 for instance, creates a presence that both asserts and undermines the condition of the object in sculpture. Projected light too has often been used by Flanagan, the source of the light, an old-fashioned slide projector sitting on the floor, is more than a mere accessory to the work but has become (especially nowadays with its retro associations) an important concrete element in the overall piece. The juxtaposition between the projected light and the length of canvas crumpled up in the corner of a room as in ‘daylight light piece 3 ’69’ 1969 depends for its presence on the way in which shadows highlight shape as they play upon the material, along with the immateriality of the light that is nevertheless dependent upon the solid wall of the gallery in order to prevent it from becoming completely invisible and disappearing into the atmosphere.

Anne Tallentire was brought up in Northern Ireland and the early experience of being raised in such a divided and complex community has affected her thinking as an artist and contributed to an awareness of inequality and political friction. Her works have been noted for their concern with issues of displacement and dislocation and an examination of social justice and civic space expressed through moving image; performance; installation and photography. Alongside this runs an approach to materials that is rooted in Tallentire’s nascent interest in Arte Povera, an interest that contributes to her concern generally in making visible what often goes unnoticed in daily life. Tallentire uses materials and the orchestration of concrete elements as a political statement. By dismantling and re-assembling everyday materials she elevates humble stuff from the building site, for example, into the focus of the public gaze and starts to reveal the unstated power and status that stems from their employment. Tallentire’s concern with space and its function is demonstrated by the formal arrangement of her installations. Not only physically or geographically (although Situationist psychogeography surely has a part to play here)[1] but also with the potential such space and materials have to give voice to those overlooked by the mores of mainstream society. Tallentire’s work ‘concerns not so much who is speaking? But, what is it to speak? Not so much where do I speak from, as what is the nature of this speaking? [2]

In Tallentire’s assemblage GF3-3, 2018 she juxtaposes two elements, a photograph taken during the building of a youth centre in Calais in January 2016 and materials corresponding to those used in its construction. The apparently informal arrangement of the installation in which sheets of OSB (orientated strand board) are leant against the wall or lie on the floor evokes the precarious condition of the situation (in this instance the plight of refugees and migrants in the Calais Migrant camp). The title of the work is taken from a mark, hand written on the board in the production factory, indicating that three panels are designated for a ground floor storey. The photograph of similar OSB boards lies in the assemblage making an interesting association within the canon of Conceptual art with Victor Burgin’s work from 1967, Photopath.[3] Like this, it produces a tension between image and object, material and depiction, as it extends the spatial, temporal and political dialogue that underpins Tallentire’s work. Accompanying GF3-3 in the exhibition is Shelter Notes, 2016 a publication that Tallentire produced as part of her project Shelter, 2016[4], in which the

[1] How do different places make us feel and behave? The term psychogeography was invented by the Marxist theorist Guy Debord in 1955 in order to explore this.

www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/psychogeography

[2] Jean Fisher. Dancing on a tightrope (for Anne Tallentire), Anne Tallentire, Valerie Connor (ed.), Project Press, Dublin.1994

[3] Victor Burgin, Photopath 1967, was installed in the exhibition When Attitudes Become Form, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 1969.

[4] A 14-18 NOW / Nerve Centre Derry commission

construction of the Nissen hut, the archetypal form of basic shelter for the displaced since WW1, was explored in the context of a new humanitarian crisis. Shelter is devised to be shown, ideally, in outside and internal spaces, the materials used for a contemporary equivalent of a Nissen hut’s fabrication are assembled, disassembled, re-assembled and the process filmed. Shelter Notes is a record of the thinking behind the process of the work.

Among the core principles listed above that underpinned Conceptual art are an analysis of language; the poetic potential inherent in everyday objects; an anti-authoritarian attitude; a questioning of the nature of art. All can be applied to the practice of Fiona Banner aka The Vanity Press. Central to which is an exploration of the inexhaustible semantic permutations of units of language; their ambiguities, structure and concrete presence. To which she adds another somewhat marginalised characteristic of much Conceptual art, the capacity to play with ideas in a humorous and poetic way. The full nomenclature for Fiona Banner is Fiona Banner aka The Vanity Press. The acronym ‘aka’ fits well into her canon. Publishing is central to her practice and she often produces books under her own imprint. In 1997 Fiona Banner aka The Vanity Press produced a 1000 page book, ‘The NAM’, while not an acronym in itself but rather a simple abbreviation, nevertheless this distillation of the Vietnam War and the title of a Marvel comic has been appropriated by Fiona Banner aka The Vanity Press to detail scene by scene the transcripts of six blockbuster films about the War. Fiona Banner aka The Vanity Press is concerned with the way in which words and punctuation can be reduced to the minutiae of their form and thus set up a changed meaning. Meaning that is, however, forever associated with a Western code such is the depth of our familiarity with its origins. Word codes and systems are manipulated, concentrated, expanded and concretised by Fiona Banner aka The Vanity Press and the acronym is a simple example of how this can occur. But unlike the dematerialisation of the object, a necessary condition of Conceptual art, she turns the insubstantiality of a sequence of letters, words, or symbols into a massive celebration of material. The world is translated in all its absurd horror and humour into words and back again. ‘Portrait of an Alphabet’, 2009 is a column of photo booth snaps taken of each letter in the alphabet. It makes the universality of the capital letter intimate, as letters replace the usual head and shoulders mug shot normally associated with a personal moment. Editions of her books become sculpture, stacked up in columns or piled high.

The material substance of Fiona Banner aka The Vanity Press’s work can manifest on a vast scale as in the presence of ‘Falcon 59400 pt’, a 3.3 x6.5 metre Pneumatic ship's fender, balanced on books, installed in Frith Street Gallery in 2019, or in ‘Harrier and Jaguar’ 2010, for which she placed recently decommissioned fighter planes in the neo-classical setting of the Duveen Galleries at Tate Britain, a setting redolent of power and empire. These objects represent the 'opposite of language', used when communication fails. The fascination of Fiona Banner aka The Vanity Press with the impossibility of language vying with the impossibility of the image are taken full circle; the planes are accompanied by 170 page book published by the Vanity Press ‘All the World’s Fighter Planes’ 2004. In Banner’s hands ‘things’ become ‘publications’. ‘Nought Poem’, 2018 reads like a concrete poem. The sun sets on this helicopter tale blade as the colours of the ISBN that relates specifically to this publication are spelt out in a spectrum of pale yellow to deep red. An ISBN provides the unique identity that a publication needs as a symbol of its authenticity and by tattooing one on her lower back in ‘Portrait of the Artist as a Publication’ 2009 –‘ she has officially registered herself as a publication – ‘Fiona Banner’[1] Her most recent work in Extrospection is ‘23 March - 4 July 2020’, it continues the interest that Fiona Banner aka The Vanity Press has in publishing under her personal ISBN. An image of the ISBN is made by laying the letters and numbers of which it is comprised onto a sheet of paper and exposing it to the sun in a process similar to that of the pictogram. The exposure took place over the period of the lockdown in England. The dates of which are the title of the work.

Notions of impossibilities of language and image are echoed in Cally Spooner’s writing. Her performances, radio plays and films are subject to a process of constant revision in an attempt to reach a conclusion that is constantly challenged in its promise to deliver anything conclusive. Spooner bases her works upon extensive research, a gathering of material from which she then creates narratives and scripts that are rendered into live works. These live actions in which Spooner may act as either publisher, producer, director, scriptwriter and collaborator, or all, take as their premise the unlikelihood that norms of conventional theatre can deliver a truly determinable account of the nuanced complexity of modern life. For Spooner, the probability that such a lack of resolution, incomplete in its presentation and oblique in language, has the potential to convey and portray more accurately the anxieties of performance, and by extension contemporary life, than the definable resolution inherent in orthodox theatre.

In her 2013 musical, produced first as a live performance and later as a film, ‘And You Were Wonderful, On Stage’, Spooner critiques the way society has become prey to forms of technological dependency. This dependence, that we might all find ourselves subject to, whereby the general public is duped by powerful advertising memes into believing that an altered version of certain events casting the protagonists in a good light is in fact true, also reflects a societal dependence upon influential and powerful people. She cites the examples of Beyonce lip-syncing at Barak Obama’s Presidential Inauguration rather than singing live, and Lance Armstrong’s faking of his cycling achievements, then much later confessing to them on the Oprah Winfrey show in a staged performance, as examples of such failures of authenticity presented as the truth. The complete work consists of five acts each of which refers to a separate but similar lapse in integrity subsequently presented to a supposedly gullible public as the truth. Her later work from 2016 ‘On False Tears and Outsourcing’ censures the surreptitious influence of management policy occasioned by

[1] “The tattoo is my own personal ISBN (International Standard Book Number);I am officially registered as a publication – ‘Fiona Banner aka The Vanity Press’. It’s not really about branding, but how works of art act as mirrors; it’s also about stories and biography – the conspiracy of narrative. It was thinking also about copyright and publishing in a jokey, serious way. A sort of portrait as book.” Fiona Banner aka The Vanity Press quoted on the artist’s website http://www.fionabanner.com/works/isbnfiona/index.htm?i22

Google’s corporate strategies in the business world and Spooner’s earlier experiences working as a copywriter in an advertising agency. This is presented in a gallery context with a group of dancers who have been trained by a rugby coach and a film director to learn a series of movements that derive from management strategies, contact sports and even film romance. This incongruous association of actions binds the dancers together while ensuring they each retain a separate identity that will not be absorbed by the group. The individual is valued but only if they work well as a member of the team.

‘Off Camera Dialogue’ 2014, shown in ‘Extrospection’, also utilises Spooner’s experience from her days in advertising. The work is based on a failed out-take discovered by Spooner when she was working as a copywriter. The off-camera transcript is taken from a company employee’s response to a management request to present his personal background and aspirations. As he delivers his presentation, an interviewer who tweaks his style and corrects his speech in order to tailor it to better fit a smoother corporate image coaches the hapless employee. The dialogue was rejected for commercial use and later found by Spooner in whose hands the nonverbal nature of this awkward delivery is accentuated by the anonymity of the central character, a faceless and impersonal presence who is constantly interrupted by a female chorus repeatedly admonishing him to rehearse his dialogue once more. As in much of Spooner’s work the technical mishap is a recurring theme, in one instance as technological fraud perpetrated on a credulous public, in another as competitive management tactics applied to dance. The constant revision of each collective production probes the rehearsal as an end in itself.

The artists included in Extrospection are drawn from different generations, from those instrumental in establishing Conceptual art as a discipline to those active today. Most recently Toby Tobias Kidd is generating a practice that draws upon his earlier life as a pop musician. He too often works collaboratively and is one part of a loose artists’ collective ‘Pragmata’ with Adele Lazzeri that was formed out of a project in Zagreb in 2017. The two work on projects together slowly evolving a joint practice sitting outside yet within their two personal artistic preoccupations. Kidd’s collaborative projects extend into performance in which pop songs are hijacked (he has formed his own record company, Crocodile Laboratories, that produces sound works and stripped down versions of songs from earlier projects); the publishing of an artists’ journal ‘Fiends’ available by subscription; musicality in grass roots politics; all of which are initiatives aimed at considering the future of art in the public sphere. ‘sometimes personal but relate to social; networked, entangled, technological; performed, prescriptive, perchance; researching, learning’.[1]

The public dimension of art practice underpins Kidd’s work and its place in the realm of public event is important to its realisation. His work ‘The Blossom’ was created as an online project during the early days of the Covid-19 crisis. It takes the form of a fictional dialogue between a woman and a man who has returned to his home after an absence of two years to find it occupied by the woman. An

[1] Artist’s statement provided to the author, August 2020

exchange ensues between them about property, ownership and profit within capitalism, posited by the man as an idealistic system. As they discuss the meaning of a house, of a home, text is superimposed visually over the sound of their conversation summarizing what is being discussed. The language employed by the two protagonists illustrates Kidd’s interest in the way language is navigated at an ideological level; technical jargon and ordinary language, emotion and structural hierarchies. As he says, ‘Text and speech become the material that mutates into a multi-headed monster, a mash-up of pop-songs hijacked for partisan means, collective structural investigations, stories of economic crises, and imagined future anarchist parks. The performance and re-performance of these gestures are part of the process of their production, the infinite potential of repetition, and reinterpretation.’

This essay considers Conceptual art through the work of several artists, whose practice has either provided a benchmark for Conceptual art or builds on the premise that it is more than just ‘ideas generated’ art: it is formed by the extrospective observation of things external to the artist. The term extrospection invites the viewer to consider an opposite of introspection and it is used in this instance to categorise art that is not solely about the artist’s own mental processes. In correspondence with the author, John Latham’s son Noa Latham wrote ‘My projection onto the term (extrospection) was to take the reflective state of something seeming to be so with a great sense of personal conviction and switch the something that seems to be so from one’s own mental state to a feature of the world. The term captures art that is not about the artist’s own mental processes and suggests that it is about a broader range of art than what is about art and its place in the world’. Whether or not Conceptual art died in the 1970s hardly seems an issue any longer. Victor Burgin thought that by 1973 Conceptual art had become the last gasp of formalism and that artists needed to do something more than engage in a discursive process. Conceptual art now takes the form of projects rather than documents as is exemplified by those artists in ‘Extrospection’ practicing today and its condition, while often retaining the Utopianism that characterized the first generation of Conceptual artists, uses the structures, codes and institutions of the world as its system. Its concerns lie in a communality that recognizes the importance of communication and human behaviour. A legacy of a deep-rooted praxis of interrogation.

David Thorp, October 2020, London

-

Cally Spooner, Off Camera Dialogue, 2014, Three channel HD video, Duration: 6min.

Courtesy: Collection Frac Franche-Comté © Cally Spooner, credit photo Blaise Adilon

-

-

Fiona Banner, Nought Poem, 2018, Paint, Merlin Tail blade, Published by The Vanity Press, 2020, 177 x 40 cm

Courtesy: The artist and Frith Street Gallery, London -

Toby Tobias Kidd, The Blossom, 2020, Video and Audio, duration: 8:28 min.

Courtesy: The artist

-

John Latham, Rephrase: 'zero space, zero time, infinite heat', 2005, Vinyl text, Dimensions variable

Courtesy: John Latham Estate and Lisson Gallery, London -

Anne Tallentire, GF3-3, 2018, OSB boards and photograph, 90 x 207.5 x 165 cm

Courtesy: The artist and Hollybush Gardens, London

“Conceptual artists leap to conclusions that logic can not reach”

-Sol LeWitt

Pi Artworks London is pleased to announce EXTROSPECTION curated by David Thorp. EXTROSPECTION is 2020-21 season opening show of the gallery and coincides with Frieze London week.

EXTROSPECTION brings together works from Fiona Banner aka The Vanity Press , Barry Flanagan, Toby Tobias Kidd, John Latham, Cally Spooner, Anne Tallentire.

Conceptual art was an international movement and, after New York, London was an important centre. The artists selected for EXTROSPECTION all have a strong link to London. They are drawn from different generations, from those instrumental in establishing conceptual art as a discipline to those active today.

Over the years Conceptual art has come to be used as a popular catch all for everything that isn't conventional painting and sculpture. But did Conceptual art actually run its course by the 1970s? Or has it endured as a distinct discipline that manifests core principals such as an analysis of language; the poetic potential inherent in everyday objects; an anti-authoritarian attitude; a questioning of the nature of art. Using the structures, codes and institutions of the world as its system? A distinct discipline formed by the extrospective consideration of things external to the artist; putting ideas about art and its place in the world over the artists' mental and emotional processes?

EXTROSPECTION runs between 1 October - 14 November 2020.

For more information and all enquiries please contact Pi Artworks London at london@piartworks.com

David Thorp is an independent curator. He has been the Director of Chisenhale Gallery, London; The Showroom, London; The South London Gallery; Curator of Contemporary Projects at the Henry Moore Foundation as well as working internationally on a variety of contemporary art projects for a portfolio of arts organisations.

Fiona Banner aka The Vanity Press, born in 1966, Merseyside, England, lives in London, explores gender, collections, and publishing through a practice spanning forms as varied as drawing, sculpture, performance, and moving image. In 1997 she started her own publishing imprint The Vanity Press, which has been the backbone of her work ever since. Banner toys with the snobbery inherent in the title by publishing posters, books, objects and performances that deploy a playful attitude and utilise pseudo grandeur.

Barry Flanagan, born in 1941, Prestatyn, Wales, died in 2009, Ibiza, Spain, is widely acknowledged as one of the leading innovators in sculptural practice to have emerged from St Martins School of Art in the mid 1960s, before this he had already experimented extensively with concrete poetry. In one of his notes Flanagan described his sculptural practice as akin to ‘the poet of the building site.’. Flanagan’s experimentation with methods and materials remained central to his practice and he continued to extend and to question the range of sculptural properties.

Toby Tobias Kidd, born in 1981 Newtown, Wales, lives in London, is interested in the way we navigate language at an ideological level; technical jargon and ordinary language, emotion, and structural hierarchies. Text and speech become the material that mutates into a multi-headed monster, a mash-up of pop-songs hijacked for partisan means, collective structural investigations, stories of economic crises, and imagined future anarchist parks.

John Latham, born in 1921, Livingstone, Northern Rhodesia (now Maramba, Zambia), died in 2006 London, was a pioneer of British conceptual art, who, through painting, sculpture, performances, assemblages, films, installation and extensive writings, fuelled controversy and continues to inspire. A visionary in mapping systems of knowledge, whether scientific or religious, he developed his own philosophy of time, known as ‘Event Structure.’ In this doctrine he proposed that the most basic component of reality is not the particle, as implied by physics, but the ‘least event,’ or the shortest departure from the state of nothing.

Cally Spooner, born in 1983, London, England, lives in London and Athens, her work consists of media installations, essays, novels and live performances such as radio broadcasts, plays and a musical, which grapple with the organisation and dispossession of that which lives. She often uses rehearsals, or the episodic form, as a means, and an end, in itself.

Anne Tallentire, born in 1950, Ireland, lives in London, is working with moving image, sculpture, installation, performance and photography. Through visual and textual interrogation of everyday materials and structures, she seeks to reveal systems that control the built environment, affect displacement and shape the economics of labour.